Editor’s Note: This blog was updated in August 2023 with the latest information about the potential harms of Aspergillus contamination on cannabis.

While there have been no documented fatal overdoses from cannabis in the 39 states that have legalized its use, there have been more than two dozen documented cases of cannabis users acquiring aspergillosis from cannabis products contaminated with pathogenic Aspergillus spores. Some of those cases have even led to death.

News articles, video interviews, and lawsuits have argued that Aspergillus testing on cannabis products is not necessary, but we could not disagree more. Aspergillus contamination is responsible for the only documented cannabis-related deaths, and testing for pathogenic Aspergillus species is essential to ensuring consumer safety.

What is Aspergillus?

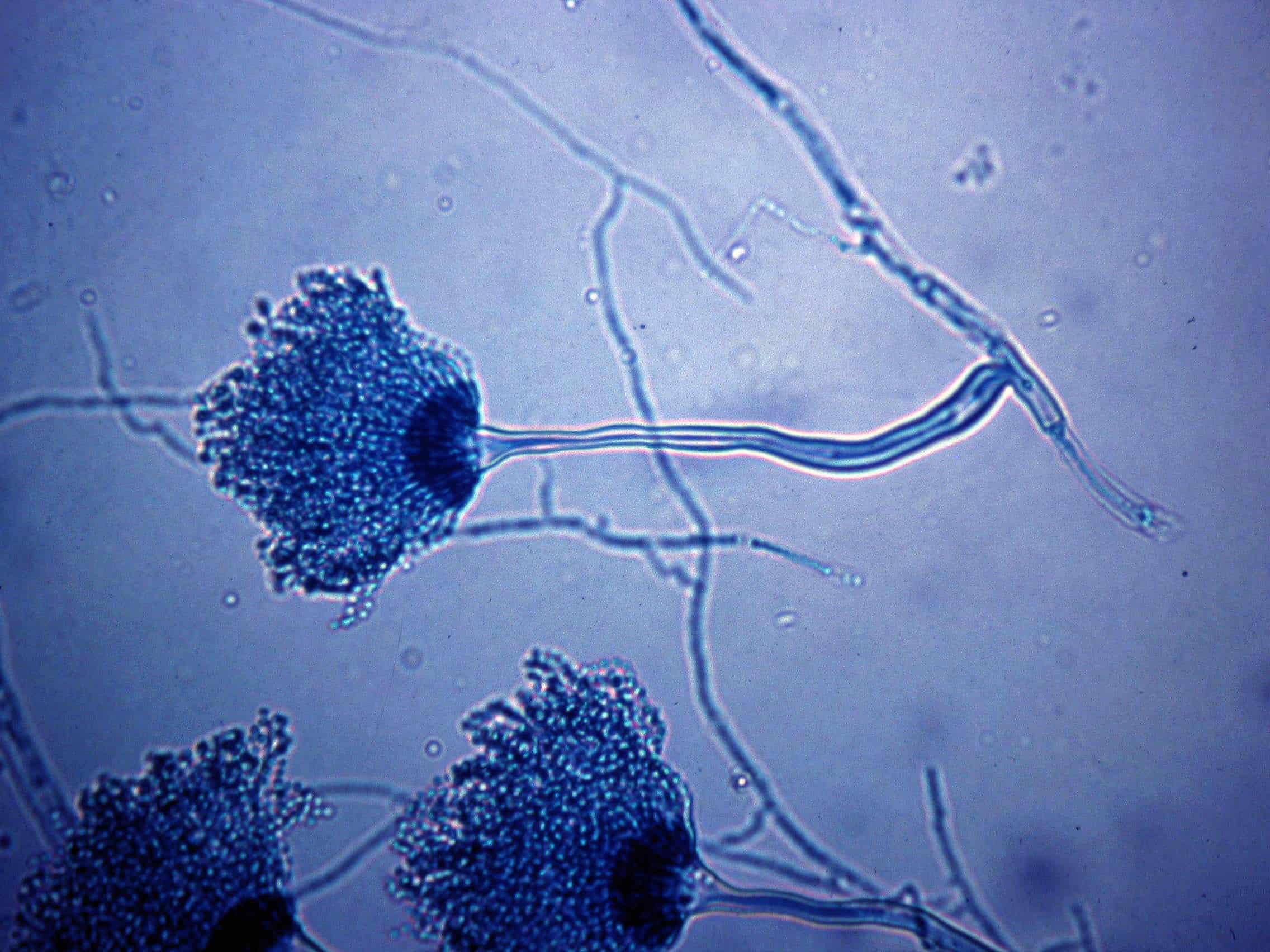

Aspergillus is a filamentous fungi that is most commonly found in soil and decaying vegetation. Its spores propagate rapidly in the air with each fungus capable of producing thousands of conidia. These spores are commonly spread through environmental disturbances and strong air currents, that allow them to be found both indoors and out. Aspergillus spores are tiny, even by biological standards, allowing them to travel great distances in the air.

Is Aspergillus harmful to humans?

While most healthy people will breathe in Aspergillus spores every day without getting sick, there are a handful of pathogenic species (A. flavus, A. fumigatus, A. niger, and A. terreus) that can cause different types of Aspergillosis infections, ranging from mild to potentially fatal. The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention lists the following types of Aspergillosis.

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA): Occurs when Aspergillus causes inflammation in the lungs and allergy symptoms such as coughing and wheezing, but doesn’t cause an infection. [reference]

- Allergic Aspergillus sinusitis: Occurs when Aspergillus causes inflammation in the sinuses and symptoms of a sinus infection (drainage, stuffiness, headache) but doesn’t cause an infection. [reference]

- Azole-Resistant Aspergillus fumigatus: Occurs when one species of Aspergillus, A. fumigatus, becomes resistant to certain medicines used to treat it. Patients with resistant infections might not get better with treatment.

- Aspergilloma: Occurs when a ball of Aspergillus grows in the lungs or sinuses, but usually does not spread to other parts of the body.[reference] Aspergilloma is also called a “fungus ball.”

- Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: Occurs when Aspergillus infection causes cavities in the lungs, and can be a long-term (3 months or more) condition. One or more fungal balls (aspergillomas) may also be present in the lungs.[reference]

- Invasive aspergillosis: Occurs when Aspergillus causes a serious infection, and usually affects people who have weakened immune systems, such as people who have had an organ transplant or a stem cell transplant. Invasive aspergillosis most commonly affects the lungs, but it can also spread to other parts of the body.

Are cannabis users at risk for Aspergillosis?

Since Aspergillosis infections occur via inhalation of spores, ensuring that inhaled cannabis products do not contain pathogenic Aspergillus is critical to ensuring consumer safety. A 1983 study isolated Aspergillus fumigatus spores from cannabis smoke, indicating the spores do in fact survive combustion.

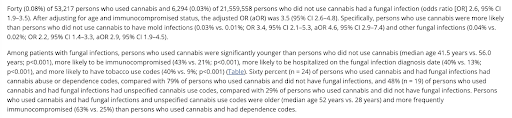

A 2020 study published by the CDC found that cannabis users are 3.5 times more likely to acquire fungal infections. This data was derived from a large insurance database (over 50,000 patients) that linked ICD10 codes to cannabis users. Aspergillosis was measured in the study.

Is there a clear, established link between the consumption of contaminated cannabis products and Aspergillus-related health issues?

Yes. There are dozens of peer-reviewed cases documenting the dangers of pathogenic Aspergillus in cannabis patients.

The documented cases describing Aspergillosis from contaminated cannabis vastly outnumber the published clinical risks for every other contaminant for which the cannabis industry tests.To date, there simply are no documented deaths for cannabis-derived heavy metals, mycotoxins, pesticides or incorrect cannabinoid labeling.

Does Aspergillosis only occur in the immunocompromised?

No. While the immunocompromised are certainly at higher risk of acquiring invasive Aspergillosis infections, immunocompetent cannabis users are not invulnerable to the harms of pathogenic Aspergillus.

For example, Zaga et al and Kang et al both describe cases of Aspergillosis in immunocompetent cannabis users. While not in a cannabis user, the Shapiro et al case describes an immunocompetent cannabis user, who developed cryptococcal meningitis from Pre-rolls. Additionally, the CDC published a study showing cannabis users are 3.5 times more likely to acquire a fungal infection, and included cases of immunocompetent patients acquiring aspergillosis.

Which US jurisdictions require testing inhaled cannabis products for pathogenic Aspergillus?

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Guam

- Hawaii

- Iowa

- Michigan

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nevada

- New Mexico

- New York

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- South Dakota

- Utah

- Vermont

- West Virginia

View our Cannabis Microbial Testing Regulations by State page for more information on each state’s requirements.

Are Aspergillus spores everywhere?

While it is true that Aspergillus is a common mold, the claim that pathogenic Aspergillus spores are ubiquitous, and therefore should not be tested for in cannabis is based on a misunderstanding of the scientific literature.

Opponents of Aspergillus testing often cite Guinea et al., which measured the amount of Aspergillus in the air during different seasons. The highest levels the authors found was 85 CFU of Aspergillus in a cubic meter of air. While this result appears to support the idea that Aspergillus is unavoidable, the study is not a model for cannabis testing for several reasons.

First, the study’s count includes all Aspergillus species (~180) and not just the four pathogenic species Oregon requires.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, the sample size measured in the Guinea et al. study (1 cubic meter) is 1 million times larger than the sample size Oregon requires for cannabis testing (1 gram). If one were to adjust for the difference in sampling size, the number of CFU in one mL of air is only .000085 CFU, which is well under the one CFU threshold.

Finally, the failure rates in states that require testing for pathogenic Aspergillus does not support the ubiquity argument. For example, in June 2023, the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission (OLCC) reported failure rates of 8% and 4.3% for cannabis flower and all products, respectively.

Why Use qPCR for Aspergillus testing on Cannabis?

In 2020, The United States Pharmacopia issued guidance on microbial testing for cannabis and in it named qPCR “by far the most sensitive” method for detecting pathogenic species of Aspergillus.

The authors point out the inadequacies of using plating to detect Aspergillus, citing that pathogenic species are often indistinguishable from their non-harmful relatives. Although not mentioned in the article, Aspergillus is also an endophyte, which makes it difficult to detect with plating methods because the plant cells are not lysed to access the pathogens living inside.

Will qPCR assays fail samples that contain DNA from dead pathogenic Aspergillus cells?

No. While it is true that a qPCR assay will detect any target DNA, regardless of viability, most commercially available Aspergillus kits, including PathoSEEK, require an enrichment step prior to PCR amplification. During this enrichment step, the sample is incubated in a growth medium for a defined time at a certain temperature. This allows viable Aspergillus spores to proliferate, making them easier to detect while also degrading any free DNA from dead cells. Testing methods that omit this step or claim it is unnecessary should be required to provide evidence of their avoidance of dead DNA.

Does Medicinal Genomics lobby state regulators to implement Aspergillus testing?

No. Medicinal Genomics does not “lobby” state regulatory agencies. However, we do submit our recommendations to regulators that solicit input during open comment periods. This is a standard practice, and something many stakeholders do, including our competitors, cannabis growers, processors, retailers, etc.

Medicinal Genomics is intensely interested in putting forth the most protective testing rules based on the best science available for inclusion in state regulations. Currently, there are 36 cannabis legal states and 27 different sets of regulations. Obviously, there is a great deal of disagreement over what constitutes “the best science” and the regulations they’re based on. Given the nascent nature of the cannabis industry, this is understandable, however unfortunate. Science is often a matter of opinion until it is proven otherwise. In the case of these four pathogenic Aspergillus species, there is a clear danger and clearly dire consequences for cannabis patients. And that is not a matter of opinion. It is proven science. If cannabis is ever going to take its rightful place in society as medicine, the industry must move toward establishing trust, confidence, and safety. Testing cannabis for pathogenic mold is just one step along that journey.

Why does Medicinal Genomics advocate for Aspergillus testing instead of total yeast and mold?

We believe that species-specific testing for known human pathogens is a better approach than total count tests, such as total yeast and mold (TYM). There are several reasons for this position.

First, there is no clinical literature linking total yeast and mold levels to clinical outcomes. Part of the reason is that one must fulfill Koch’s postulates before making such associative links. To do so, one must isolate an organism, reintroduce it to a host to recapitulate disease, and then subsequently reisolate it. This simply cannot be done for TYM and TAC as they fail to isolate a specific pathogen.

Second, not all microbes are harmful. In fact, most fungi are benign or even beneficial to human health. Which organisms are present in a sample is more important, than how many there are. For example, a cannabis sample could pass a total yeast and mold test, yet still contain thousands of pathogenic Aspergillus spores. Conversely, a cannabis sample may exceed the action limit for a total yeast and mold test, yet not contain any organisms that will cause illness.

Third, total count tests discourage growers from utilizing beneficial microbes. There are approximately two dozen biocontrol products in which the primary ingredient is either a bacterial or mold species. Growers who use organic practices prefer these products because the alternatives are harmful chemicals and pesticides. However, growers in states that have strict total limits may not be able to use these effective biocontrol products.

An article recently published by StratCann quoted an executive from a Canada testing lab, who said:

“The test for the total aerobic count doesn’t distinguish between what’s good and bad. I can’t imagine that that problem will go away, as we aren’t about to isolate thousands of bacteria. So, even if the bacteria are helpful to the plant, if the numbers are too high, it won’t pass the test.”

Test for Aspergillus with PathoSEEK

Medicinal Genomics can help labs test for Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, and Aspergillus terreus using our PathoSEEK® qPCR Detection Assays. The PathoSEEK 5-Color Aspergillus Multiplex assays were specifically designed for use on cannabis matrices and the AOAC PTM has certified its use for:

- Next-day results. 24-hour enrichment for cannabis flower

- Multiple matrices. Cannabis flower, infused edibles, and concentrates

- Multiple instruments. Aglient AriaMX and BioRad CFX96

We can also assist with validation and automation to make testing and scalable. Contact us today to get started!

Documented Cases of Aspergillosis from Contaminated Cannabis

- M.J. Chusid, J.A. Gelfand, C. Nutter, and A.S. Fauci, Letter: Pulmonary aspergillosis, inhalation of contaminated marijuana smoke, chronic granulomatous disease. Annals of Internal Medicine 82(5), 682-683 (1975). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1094876/

- R. Llamas, D.R. Hart, and N.S. Schneider, Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis associated with smoking moldy marihuana. Chest 73 (6), 871-872 (1978). https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(16)61841-X/pdf

- S. Sutton, B.L.Lum, and F.M. Torti, Possible risk of invasive aspergillosis with marijuana use during chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer. Drug Intelligence & Clinical Pharmacy 20(4), 289–291 (1986).

- R. Hamadeh, A. Ardehali, R.M. Locksley, and M.K. York, Fatal Aspergillosis associated with smoking contaminated marijuana in a marrow transplant recipient. Chest 94(2), 432–433 (1988).

- D.W. Denning, S.E. Follansbee, M. Scolaro, S. Norris, H. Edelstein, and D.A. Stevens, Pulmonary aspergillosis in the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine 324(10), 652–664 (1991).

- W.H. Marks, L. Florence, J. Lieberman, P. Chapman, D. Howard, and P. Roberts, et. al., Successfully treated invasive pulmonary aspergillosis associated with smoking marijuana in a renal transplant recipient. Transplantation 61(12), 1771–1774 (1996).

- M. Szyper-Kravitz, R. Lang, Y. Manor, and M. Lahav, Early invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a Leukemia patient linked to Aspergillus contaminated marijuana smoking. Leukemia & Lymphoma 42(6), 1433–1437 (2001).

- R. Ruchlemer, M. Amit-Kohn, and D. Raveh, et. al., Inhaled medicinal cannabis and the immunocompromised patient. Support Care Cancer 23(3), 819–822 (2015).

- D.W. Cescon, A.V. Page, S. Richardson, M.J. Moore, S. Boerner, and W.L., Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with marijuana use in a man with colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical oncology. 26(13), 2214–2215 (2008).

- A. Bal, A.N. Agarwal, A. Das, S. Vikas, and S.C. Varma, Chronic necrotising pulmonary aspergillosis in a marijuana addict: a new cause of amyloidosis. Pathology 42(2), 197–200 (2010).

- Y. Gargani, P. Bishop, and D.W. Denning, Too many moldy joints – marijuana and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases 3, 2035-3006. Open Journal System (2011).

- S.L. Kagen, M.D. Viswanath, P. Kurup, P.G. Sohnie, and J.N. Fink, Marijuana smoking & fungal sensitization. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 71(4), 389–393 (1983).

- S.L. Kagen, Aspergillus: An inhalable contaminant of marihuana. The New England Journal of Medicine 304(8), 483–484 (1981).

- J.L. Pauly and G. Paszkiewicz, Cigarette Smoke, Bacteria, Mold, Microbial Toxins, and Chronic Lung Inflammation. Journal of Oncology 819129, 1-13 (2011). 100 Cummings Center • Suite 406L • Beverly, MA 01915 • 877-395-7608 • www.medicinalgenomics.com 6

- T. L. Remington, J. Fuller, and I. Chiu. Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis in a patient with diabetes and marijuana use. Canadian Medical Association Journal 187 (17), 1305-1308 (2015) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.141412

- D. Vethanayagam, E. Saad, and J. Yehya, Aspergillosis spores and medical marijuana. Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) Letters 188(3), 217 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4754188/pdf/1880217a.pdf

- S. M. Levitz, R. D Diamond, Aspergillosis and marijuana. Annals of Internal Medicine 115(7), 578-579 (1991). https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/epdf/10.7326/0003-4819-115-7-578_2

- B. R. Waisglass, Aspergillosis spores and medical marijuana. Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) Letters 187(14), 1077 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4592303/pdf/1871077.pdf

- E. Faccioli, F. Pezzuto, A. D. Amore, F. Lunardi, C. Giraudo, M. Mammana, M. Schiavon, A. Cirnelli, M. Loy, F. Calabrese, and F. Rea, Fatal Early-Onset Aspergillosis in a Recipient Receiving Lungs From a Marijuana-Smoking Donor: A Word of Caution. Transplant International 35 (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8883434/pdf/ti-35-10070.pdf

- A. P, Salam and A. L. Pozniak, Disseminated aspergillosis in an HIV-positive cannabis user taking steroid treatment. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 17(8), 882 (2017). https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(17)30438-3/fulltext

- T. E. Johnson, R. R. Casiano, J. W. Kronish, D. T. Tse, M. Meldrum, and W. Chang, Sino-orbital aspergillosis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmology 117(1), 57-64 (1999). https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaophthalmology/fullarticle/411373

- K. Benedict, G. R. Thompson, and B. R. Jackson, Cannabis Use and Fungal Infections in a Commercially Insured Population, United States, 2016. Emerging Infectious Diseases 26(6), 1308-1310 (2020). https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/6/19-1570_article

- M. I. Shafi, S. Liaquat, and D. Auckley, Up in smoke: An unusual case of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage from marijuana. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports 25, 22-24 (2018). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221300711830008X?via%3Dihub