Several articles have been published recently describing the challenges of microbial testing on cannabis and hemp. One thing that all these articles have in common is total count tests.

It’s time that we address the elephant in the room. The truth is that total count tests are not a good indicator of cannabis and hemp product safety for the following reasons:

- Pathogenic microbes may still be present

- Testing methods often do not agree

- Growers are discouraged from using beneficial microbes

- Growers are encouraged to use remediation

We believe a better way to ensure consumer safety is to perform species-specific tests that target known pathogenic organisms, such as A. flavus, A. fumigatus, A. niger, A. terreus, shiga toxin producing E. coli (STEC), Salmonella species, and others.

What are total count tests?

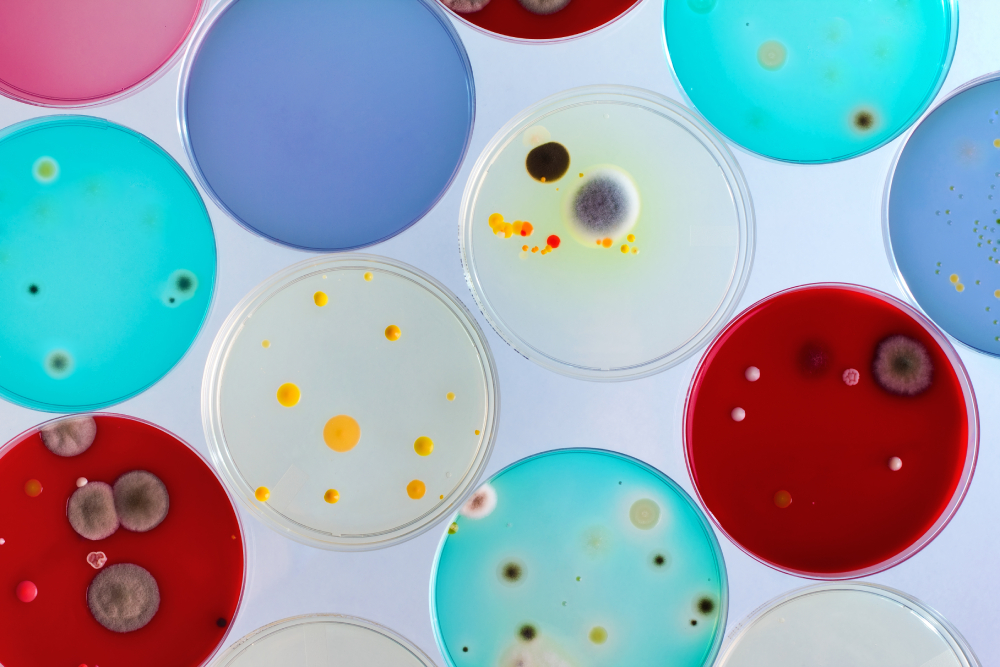

As the name suggests, total count tests are used to quantify the amount of a broad family of microbes. Common total count tests include total yeast and mold, total aerobic count, total coliforms, and bile-tolerant gram-negative bacteria.

Total Count tests are commonly used in the food industry to determine the cleanliness of a facility and its processes. However, many cannabis regulators require total count tests as a way to ensure product safety. Each state or regulatory jurisdiction that requires a total count test sets an allowable limit for the amount of colony-forming units (CFUs) that can be present in a sample.

According to our Cannabis Microbial Testing Regulations by State tool, 26 of the states that have cannabis programs require at least one total count test. However, there is little consistency when it comes to the tests they require and the limits they set.

Pathogenic microbes may still be present

Not all microbes are harmful. In fact, each human body contains approximately 40 trillion microbial cells, and almost all of them are either benign or beneficial to human life. However, adding just a hundred shiga toxin producing E. coli cells can cause serious disease. Following that logic, one must conclude that the number of microbes present on a sample can’t be the only indicator of product safety. What organisms are present on a sample is as important, if not more important, than how many there are.

For example, a cannabis sample could pass a total yeast and mold test, yet still contain a large amount of pathogenic Aspergillus, which can cause a potentially fatal lung infection. Conversely, a cannabis sample may exceed the action limit for a total yeast and mold test, yet not contain any pathogenic microbes.

A common argument for requiring total count tests is that a product with visible mold could receive a passing result. No one is arguing that cannabis flower covered with visible, non-pathogenic mold is safe, or even desirable. Instead, we would hope that distributors, retailers, and consumers would use common sense. If a product is visibly moldy, do not buy it. Would you buy moldy bread from the grocery store?

Methods do not agree

There is a certain amount of hubris that comes with assuming one could count all the yeast and mold cells on a cannabis sample. After all, we are talking about a diverse set of hundreds of different species. No method is going to effectively count all the cells present, and very few can effectively exclude bacteria from inflating their final count.

The team at Modern Canna in Florida recently demonstrated this when they performed a study to compare seven different total yeast and mold testing methods. They found that the culture-based methods produced a wide range of enumeration results, which raises the question: which result is correct?

They also discovered that the recommended incubation time for many commercially available plating methods was not long enough for all the colonies to grow. That means many labs that use culture-based methods are undercounting.

Finally, Modern Canna found that the typical dilutions performed in plating methods caused the data to be skewed because in most instances, total colonies counted at each dilution were not approximately the same. Therefore, if an average of the three dilutions was taken to determine the quantitative result, the true value may be increased or decreased depending on the skew seen.

With such inconsistency in results across different plating methods and different dilutions, how can consumers and regulators have any faith that the results of a total count test are representative of the sample?

Growers are discouraged from using beneficial microbes

There are approximately two dozen biocontrol products where the primary ingredient is either a bacterial or mold species. Growers who use organic practices prefer these products because they do not want to use harmful chemicals and pesticides. However, growers in states that have strict total limits may not be able to use these effective biocontrol products.

An article recently published by StratCann quoted an executive from a Canada testing lab, who said:

“The test for the total aerobic count doesn’t distinguish between what’s good and bad. I can’t imagine that that problem will go away, as we aren’t about to isolate thousands of bacteria. So, even if the bacteria are helpful to the plant, if the numbers are too high, it won’t pass the test.”

Why would we want to discourage growers from using organic, natural products that benefit their plants and reduce the use of harmful chemicals?

Growers are encouraged to irradiate

In states where action limits are very low, growers must irradiate crops with x-rays, electron beams, or gamma rays in order to pass.

The FDA regards irradiated food as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS); however, more research needs to be done to ensure that also applies to inhalabled products like cannabis.

A recent article published by Cannabis Now quotes Kyle Baker, co-founder Ecobuds, an industrial hygiene service for indoor cultivation facilities, as saying, “There’s degradation of materials in any type of remediation. Ozonation creates formaldehyde from organic compounds, which you don’t want to breathe in.”

And even though most irradiation method vendors claim their treatments do not lower concentrations of cannabinoids or terpenoids in the flower, Baker is skeptical. “Even irradiation isn’t fully successful without a very large dose, thereby decreasing product quality,” he said. “By definition, remediation means the product didn’t meet quality standards acceptable for market.”

Conclusion

We acknowledge that total count tests are useful tools for growers and producers as part of their good manufacturing practices to make sure their facilities and processes are clean. However, many in the industry are starting to realize that using total count tests to determine product safety may actually result in a less safe product. We would like to see a greater effort put into identifying the pathogenic organisms that are commonly found on cannabis, and developing species-specific tests to ensure they are not present in any concentration.